Contraceptive Effects

We inform, you decide.

Contraceptive Effectiveness & Side Effects

A woman tends to choose birth control based on what she considers to be the most convenient and effective method for her. However, it’s important to weigh carefully the risks and side effects of each method. Using contraceptives cannot guarantee the prevention of pregnancy. Contraceptives were used during the month of conception in 48% of unintended pregnancies. 1

Male Condom

- 82-98% effective at preventing pregnancy 2

- 60-79% effective at preventing STDs 3

Female Condom

- 79-95% effective at preventing pregnancy 4

Diaphragm or Cervical cap

- 84-94% effective at preventing pregnancy 5

- Increases risk of vaginal infection, making a woman more vulnerable to contracting STDs 6

Birth Control Pill

- 91-99% effective at preventing or terminating pregnancy 7

- Makes a woman’s reproductive tract more suseptible to infection, increasing her risk of contracting an STD by 30%. 8

- Multiplies risk of heart attack by up to 2.3 and risk of stroke by up to 2.2 9

- Increases risk of glioma, a rare brain cancer, by 50% with short-term use. Five years of birth control pill use doubles a woman’s risk. 10 (more on brain cancer)

- Listed by the World Health Organization as a Class 1 carcinogen for increased risk of breast and liver cancers 11

- For nearsighted women, six months of using the pill has been shown to increase nearsightedness 2 or 3 times. 12 (more on nearsightedness)

- More on Birth Control Pill

Depo-Provera Shot

- 94-99% effective at preventing pregnancy 13

- Associated with decreased bone mineral density, weight gain and increased risk of breast cancer 14

The Patch

- 91-99% effective at preventing pregnancy 15

- Multiplies risk of stroke by 3.2 16

Implant / IUD

- 99% effective at preventing or terminating pregnancy 17

- 47% of implant users experience adverse effects, including severe acne and weight gain 18

- More on IUDs

The Truth About Oral Contraceptives

Providers often will not furnish a full range of facts when prescribing Combined Oral Contraceptives (COC), basing the information given on their own professional opinion rather than a well-balanced presentation of the data available. Ultimately, it’s your responsibility to read the fine print.

Types of Oral Contraceptives

There are two main types of oral contraceptives: Progestin Only Pills (POP) and estrogen-progestogen pills (COC, or combined oral contraceptives). Of these, COC’s are far more commonly prescribed. “Worldwide, more than 100 million women – about 10% of all women of reproductive age – currently use combined hormonal contraceptives”.19

How COC’s Work

Combined oral contraceptives are a blend of synthetic estrogen and progesten. Unlike other forms of contraception that prevent sperm-egg contact, COC’s use a very different, 3-fold approach to birth control. The Physician’s Desk Reference states, “although the primary mechanism of [combination oral contraceptives] is inhibition of ovulation, other alterations include changes in the cervical mucus, which increase the difficulty of sperm entry into the uterus, and changes in the endometrium, which reduce the likelihood of implantation.”20 In other words, if the pill’s first two methods – inhibited ovulation and thick cervical mucus – fail to deter fertilization, its final measure of defense will cause any fertilized eggs to be prematurely aborted.

Efficiency Ratings

The pill is 92–99% effective at preventing pregnancy with perfect use.21 With typical use, 8 out of 100 women using a COC will become unintentionally pregnant each year.22 Common medications can decrease the effectiveness of oral contraceptives, including certain types of antibiotics and particularly, St. John’s wort.

COC Health Risks

One thing your doctor probably didn’t tell you is that the estrogen in COC’s is a known human carcinogen, listed among such cancer-causing agents as arsenic, tobacco and asbestos.23 According to the National Cancer Institute, COC’s “increase a woman’s risk of cervical cancer, breast cancer, and liver cancer.”24 The prevalence of HPV, a leading cause of cervical cancer, is also found to be higher among oral contraceptive users.25

Smoking while using COC’s increases your risk of heart attack, blood clots and stroke, especially in those over 35 years of age. You are up to 8 times more likely than a non-user to develop a blood clot, even if you don’t smoke. The risk is up to 3 times greater for those who use COC’s containing a progesterone called drospirenone.26

Schedule your free consultation.

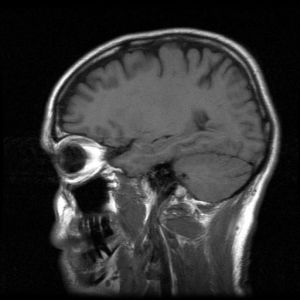

Brain Cancer and “The Pill”

A recent study published in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology27 (BJCP) aimed to prove that “oral contraceptive use influences the risks for certain cancers.” Results concluded that long-term use may increase the risk of gliomas, tumors that occur in the brain and spinal cord. This comes as a surprise to many, since estrogen and progestin were originally believed to protect against gliomas.28

Andersen and colleagues assessed over 2,000 women ages 15 to 49 diagnosed with gliomas based on their exposure to estrogen-progestagen and progestagen-only contraceptives. The study reveals that women increase their risk of gliomal brain cancer by 50% if they ever use hormonal birth control, and by 90% if they use it long-term (5 years or more).29

Named for their origin, gliomas effect the glial cells which surround and support neurons in the brain. Gliomas account for only 10% of all cancers; however, they also account for 80% of all malignant brain tumors30 and have a mere 15% survival rate.31

The bottom line is that use of synthetic hormonal agents like the birth control pill can have lasting effects on a woman’s body. Make sure that you have all of the facts you need about pregnancy prevention and your future health before you swallow The Pill.

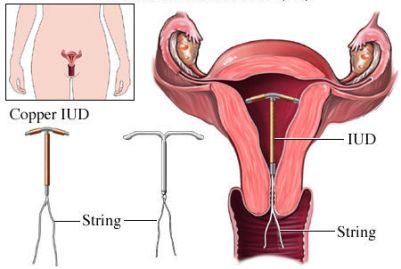

The Suggested Advantage of IUDs: Have the Risks Changed or Just Our Perception?

In an attempt to “curb teen pregnancy,”32 Golisano Children’s Hospital recently launched a campaign to promote the benefits of IUDs (intrauterine devices) over other forms of birth control.

IUDs are T-shaped plastic devices with a string attached, and come in two types: hormonal and copper. Neither of the two types of IUDs prevent ovulation. Instead, they deter sperm from reaching the unfertilized egg. Copper IUDs do this by releasing a small amount of copper into the uterus, which is believed to immobilize the sperm. Hormonal IUDs release a small amount of progestin, similar to progestin-only birth control pills. This causes the cervical mucus to thicken, making it difficult for sperm to pass. It also causes the uterine lining to thin, creating an uninhabitable environment for a fertilized egg, thus forcing it to be aborted prematurely.

Copyright © Nucleus Medical Media, Inc.

According to Dr. Greenberg, an adolescent medicine specialist at the hospital, “Today’s [IUDs] are safe, effective, invisible, and can be easily removed with no lingering effects when you decide to become pregnant.” Dr. Aligne of the Hoekelman Center goes on to say, “There’s been a lot of research about how these devices are safe for teens. But some myths from several decades ago persist, and even some doctors don’t have all the updated information.”33

However, a recent study (Sept. 2014) published by the Journal of Research in Medical Sciences34 continues to confirm that IUDs are associated with an increased risk (OR=4.39) of ectopic pregnancy. The fetal mortality rate for an ectopic pregnancy is 100%, and although available treatment methods have improved, the negative risk to future fertility is still very much a factor. Having a single ectopic pregnancy significantly lowers a women’s chances of becoming pregnant again (up to 33%),35 and also increases her risk of having additional ectopic pregnancies.

If you’re thinking about an IUD, talk to your doctor about the risks of ectopic pregnancy.

Nearsighted? Birth Control May Escalate Vision Problems

According to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists36, near-sighted women who begin taking oral contraceptives at or near puberty experience a greater loss in vision due to the estrogen-progestin pill’s potential to significantly change the shape of the cornea. Resulting issues include advanced myopia, astigmatism and Keratoconus.

Myopia by nature progresses through adolescence and plateaus in adulthood. However, in women who develop myopia (near-sightedness) at or near puberty, which in females is between the ages of 9 and 1437, oral contraceptives produced marked advancement in myopia, up to 3 times the refractive error. Refractive error is the misshaping of the cornea which causes symptoms including blurred vision, double vision, haziness, glare or halos around bright lights, squinting, headaches, or eye strain38.

Astigmatism (football-shaped cornea), a common issue which can be amended with corrective lenses, was also increased in those with a history of the ocular disorder. Those with astigmatism also had the potential to develop Keratoconus (cone-shaped cornea). Severe changes in cornea shaping caused by these issues can eliminate the option to wear contact lenses as corrective eyewear.

With less than 2% of females having had sex by the age of 12 and 16% by the age of 1539, eye health in relation to oral contraceptives is a growing concern. In a study conducted by the British Heart Foundation, it was reported that the percentage of 10 and 11-year olds who experienced some degree of myopia were as follows40:

- 2% Asian descent

- 0% African descent

- 4% Non-Hispanic Whites

It’s important to know your full health history before beginning any oral medication and be sure to get all of the facts about your birth control pill.

Medically Reviewed By:

STAFF NURSE, ROCHESTER

CINDY P., BSN, RN

1 Finer, L.B., Henshaw, S.K., (2006). Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Repro H; 38(2): 90-96.

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2011). How to prevent sexually transmitted diseases. FAQ009.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

6 Rosenberg, M.J., Davidson, A.J., Chen, J.H., Judson, F.N., Douglas, J.M., (1992). Barrier contraceptives and sexually transmitted diseases in women: a comparison of female-dependent methods and condoms. Am J Public Health; 82(5):669-674.

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

8 Rosenberg, M.J., Davidson, A.J., Chen, J.H., Judson, F.N., Douglas, J.M., (1992). Barrier contraceptives and sexually transmitted diseases in women: a comparison of female-dependent methods and condoms. Am J Public Health; 82(5):669-674.

9 Lidegaard, Ø., Løkkegaard, E., Jensen, A., Skovlund, C.H., Keiding, N., (2012). Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med; 366(24): 2257-2266.

10 Andersen, L., Friis, S., Hallas, J., Ravn, P., Kristensen, B.W., Gaist, D. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 79(4): 677-684.

11 International Agency for Research on Cancer (1999). Hormonal Contraception and Post-Menopausal Hormonal Therapy. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum; 72: 288-294.

12 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (2010). AHFS Drug Information 2010: Bethesda; MD, p. 3112.

13 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

14 Bigrigg, A., Evans, M., Gbolade, B., Newton, J., Pollard, L., Szarewski, A., Thomas, C., Walling, M., (2000). Depo Provera. Position paper on clinical use, effectiveness and side effects. Br J Fam Plann; 26(1): 52-53.

15 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Contraception. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

16 Lidegaard, Ø., Løkkegaard, E., Jensen, A., Skovlund, C.H., Keiding, N., (2012). Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med; 366(24): 2257-2266.

17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Contraception. Retrieved June 2021 from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

18 Urbancsek, J., (1998). Nonmenstrual adverse events with Implanon®. Contraception; 58: 109S-115S.

19 World Health Organization & the International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2007). Combined estrogen-progestogen contraceptives and combined estrogen-progestogen menopausal theraby. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum; 91:1-528.

20 PDR Network (2010). Precise Monagraph. Ortho Tri-cyclen, Mechanism of Action. Retrieved June 2021 from Ortho Tri-Cyclen/Ortho-Cyclen (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate) dose, indications, adverse effects, interactions… from PDR.net

21 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Contraception. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/contraception.htm

22 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. Retrieved June 2021 from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr59e0528a1.htm

23 American Cancer Society (2019). Known and Probable Human Carcinogens. Retrieved June 2021 http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CancerCauses/OtherCarcinogens/GeneralInformationaboutCarcinogens/known-and-probable-human-carcinogens

24 National Cancer Institute (2018). Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk. Retrieved June 2021 from Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills) and Cancer Risk – National Cancer Institute

25 International Agency for Research on Cancer (1999). Hormonal Contraception and Post-Menopausal Hormonal Therapy. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum; 72: 288-294.

26 NIH, NLM. (2015). Estrogen and Progestin (Oral Contraceptives). Retrieved June 2021 from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a601050.html

27 Andersen, L., Friis, S., Hallas, J., Ravn, P., Kristensen, B.W., Gaist, D. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 79(4): 677-684.

28 Haghighat, N., Oblinger, M.M., McCandless, D.W., (2004). Cytoprotective effect of estrogen on ammonium chloride-treated C6-glioma cells. Neurochem Res; 29(7): 1359-64.

29 Andersen, L., Friis, S., Hallas, J., Ravn, P., Kristensen, B.W., Gaist, D. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 79(4): 677-684.

30 Vredenburgh, J.J., Desjardins, A., Reardon, D.A., Friedman, H.S., (2009). Experience with irinotecan for the treatment of malignant glioma. Neuro-Oncology; 11(1): 80-91.

31 Ho, V.K., Reijneveld, J.C., Enting, R.H., Bienfait, H.P., Robe, P., Baumert, B.G., Visser, O., (2014). Changing incidence and improved survival of gliomas. Eur J Cancer; 50(13): 2309-18.

32 Andersen, L., Friis, S., Hallas, J., Ravn, P., Kristensen, B.W., Gaist, D. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 79(4): 677-684.

33 Haghighat, N., Oblinger, M.M., McCandless, D.W., (2004). Cytoprotective effect of estrogen on ammonium chloride-treated C6-glioma cells. Neurochem Res; 29(7): 1359-64.

34 Andersen, L., Friis, S., Hallas, J., Ravn, P., Kristensen, B.W., Gaist, D. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol; 79(4): 677-684.

35 Vredenburgh, J.J., Desjardins, A., Reardon, D.A., Friedman, H.S., (2009). Experience with irinotecan for the treatment of malignant glioma. Neuro-Oncology; 11(1): 80-91.

36 Ho, V.K., Reijneveld, J.C., Enting, R.H., Bienfait, H.P., Robe, P., Baumert, B.G., Visser, O., (2014). Changing incidence and improved survival of gliomas. Eur J Cancer; 50(13): 2309-18.

37 Stöppler, M.C., (2014). Puberty. MedicineNet, Inc. Retrieved June 2021 from http://www.medicinenet.com/puberty/article.htmm/puberty/article.htm.

38 National Institutes of Health (2014). Refractive Errors. Retrieved June 2021 from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/refractiveerrors.html.

39 Finer, L.B., Philbin, J.M., (2013). Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics; 131(5): 886-891.

40 Rudnicka, A.R., Owen, C.G., Nightingale, C.M., Cook, D.G., Whincup, P.H (2010). Ethnic differences in the prevalence of myopia and ocular biometry in 10- and 11-year-old children: The Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci; 51(12): 6270-6276.